What is the opposite of faith? – Kim Fabricius

Posted: June 29, 2015 Filed under: The Good News According to...., Theology | Tags: faith Leave a commentSermon for the 4th Sunday after Pentecost (text: Mark 4:35-41)

What is the opposite of faith?

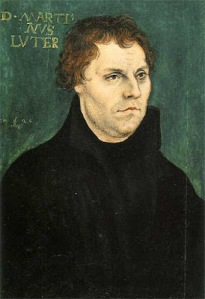

Let’s start with the Protestant no-no: works. We are justified, put right with God not by works but by faith, faith alone – sola fide – isn’t that, as Luther put it, the doctrine by which the church stands or falls? And wouldn’t Calvin and Wesley agree? Well, yes, but … Luther was citing Paul, but during the last half century – through a better understanding of the thought-world of first century Judaism – it’s now become pretty clear that what Paul meant by “works” and what Luther meant by “works” are not identical.

Conceptions of God: Feser

Posted: October 2, 2014 Filed under: Apologetics, New Atheism, Theology | Tags: Aquinas Leave a comment“Many secularists seem hell-bent (if you’ll pardon the expression) on pretending that religious people in general believe in a God so anthropomorphic that only a child or the most ignorant peasant could take the question of His existence seriously even for a moment.” [SNIP] ” To understand what serious religious thinkers do believe, we might usefully distinguish five gradations in one’s conception of God.

1) God is literally an old man white a white beard, a kind if stern wizard-like being with very human thoughts and motivations who lives in a place called Heaven, which is like the places we know except for being very far away and impossible to get to except through magical means.

2) God doesn’t really have a bodily form, and his thoughts and motivations are in many respects very different from ours. He is an immaterial object or substance which has existed forever, and (perhaps) pervades all space. Still, he is, somehow, a person like we are, only vastly more intelligent, powerful, and virtuous, and in particular without our physical and morel limitations. He made the world the way a carpenter builds a house, as an independent object that would carry on even if he were to “go away” from it, but he nevertheless may decide to intervene in its operations from time to time.

3) God is not an object or substance alongside other objects or substances in the world; rather, He is pure being or existence itself, utterly distinct from the world of time, space, and things, underlying and maintaining them in being at every moment, and part from whose ongoing conserving action they would be instantly annihilated. The world is not an independent object tin the sense of something that might carry on if God were to “go away”; it is more like the music produced by a musician, which exits only when he plays and vanishes the moment he stops. None of the concepts we apply to things in the world, in clouding to ourselves, apply to God in anything but the analogous sense. Hence, for example, we may say that God is “personal” insofar as He is not less than a person, the way an animal is less than a person. But God is not literally “a person” in the sense of being one individual thing among others who reasons, chooses, has moral obligations, etc. Such concepts make no sense when literally applied to God. Read the rest of this entry »

Propositions on Christian Theology: A Pilgrim Walks the Plank

Posted: April 29, 2014 Filed under: Currently reading..., The Good News According to...., Theology | Tags: theology Leave a commentBrilliant, pithy reading from a United Reformed Church minister in England.

That is all.

In this little book, a kind of contemporary enchiridion, Kim Fabricius engages some of the main themes of Christian theology in prose, poetry, and song (his own hym

ns). It does not aim to be systematic or comprehensive; rather it goes straight to the main contested areas in the church today, the red-button issues in doctrine, spirituality, culture, ethics, and politics. Fabricius’s imaginative vision and lively conversational style moving freely between the interrogative and the polemical, the playful and the profound invite us all to the vertiginous experience of faith. The book’s concise format and no-nonsense approach make it a perfect guide for inquiring Christians as well as committed disciples and an ideal discussion-starter for both church groups and college classes. The author’s passionate commitment to a self-critical faith is a provocative invitation to religion’s cultured despisers to join him if they dare on the plank.

For a sneak peak web version try Ben Myer’s blog

http://www.faith-theology.com/2006/09/propositions-by-kim-fabricius.html

David B. Hart on Suffering and Theodicy

Posted: March 20, 2013 Filed under: Articles, Theology | Tags: Suffering, theodicy, theology Leave a commentBut what makes Ivan’s argument so disturbing is not that he accuses God of failing to save the innocent; rather, he rejects salvation itself, insofar as he understands it, and on moral grounds. He grants that one day there may be an eternal harmony established, one that we will discover somehow necessitated the suffering of children, and perhaps mothers will forgive the murderers of their babies, and all will praise God’s justice; but Ivan wants neither harmony—“for love of man I reject it,” “it is not worth the tears of that one tortured child”—nor forgiveness; and so, not denying there is a God, he simply chooses to return his ticket of entrance to God’s Kingdom. After all, Ivan asks, if you could bring about a universal and final beatitude for all beings by torturing one small child to death, would you think the price acceptable?

Voltaire’s poem is not a challenge to Christian faith; it inveighs against a variant of the “deist” God, one who has simply ordered the world exactly as it now is, and who balances out all its eventualities in a precise equilibrium between felicity and morality. Nowhere does it address the Christian belief in an ancient alienation from God that has wounded creation in its uttermost depths, and reduced cosmic time to a shadowy remnant of the world God intends, and enslaved creation to spiritual and terrestrial powers hostile to God. But Ivan’s rebellion is something altogether different. Voltaire sees only the terrible truth that the actual history of suffering and death is not morally intelligible. Dostoevsky sees—and this bespeaks both his moral genius and his Christian view of reality—that it would be far more terrible if it were.